Lawsuits have sprung up nationwide against state and local authorities who have imposed shutdown orders in an effort to thwart the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here in Washington, two lawsuits challenging our state’s shutdown order have been filed. The first, by gubernatorial candidate Joshua Freed, was voluntarily dismissed after Mr. Freed was reassured that his backyard Bible studies would not result in enforcement action. The second, by a group of GOP legislators, is pending. But as of this writing no immediate relief has been sought by the legislators who brought that lawsuit.

As Washington begins to see progress and some counties have already moved to Phase 2 of Governor Inslee’s May 4 Safe Start Washington, many churches are asking whether the ongoing ban of in-person worship services or spiritual gatherings is legal.

We believe that Governor Inslee’s plan for Phase 2 is unconstitutional as presently drafted.

The reason is relatively straightforward: the Governor’s proclamation burdens the fundamental right to free exercise of religion. Because it burdens free exercise, the proclamation must be either generally applicable to everyone or narrowly tailored to meet a compelling state interest. Governor Inslee’s planned Phase 2 is neither generally applicable nor narrowly tailored. Therefore it is unconstitutional.[1]

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects the free exercise of religion. Free exercise is recognized as a “fundamental right,” a legal term of art that singles out a special class of rights. But the government can still burden fundamental rights in some situations. Since the 1990 U.S. Supreme Court case of Employment Division v. Smith, a “generally applicable” law may be[2] constitutional even if it interferes with a fundamental right. So a quarantine or shelter-in-place order that burdens everyone will likely be deemed constitutional even if it prevents religious assembly. As the Supreme Court said in Prince v. Massachusetts in 1944: “[t]he right to practice religion freely does not include the liberty to expose the community . . . to communicable disease.”

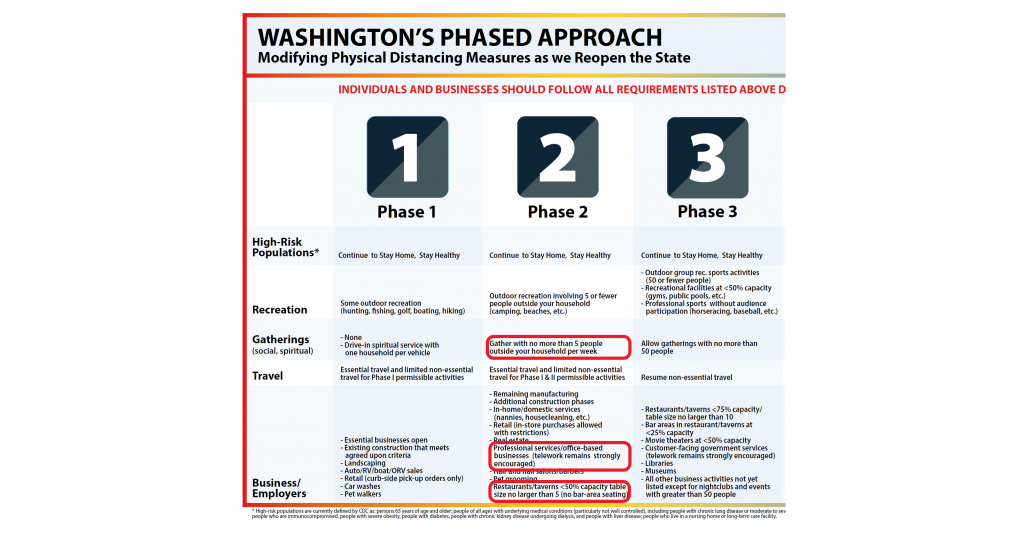

But where a law is filled with exceptions, it is no longer “generally applicable.” In this case, Phase 2 of Governor Inslee’s proclamation allows offices and restaurants to open with no fixed cap on the number of people congregating indoors. But it limits spiritual gatherings to no more than five people:

The proclamation also permits all sorts of other activity in Phase 2 as well. And the state is regularly releasing requirements for specific types of activity based on the government’s assessment of those activities. Because the law permits indoor assembly of more than five people in some contexts but not others (despite epidemiological evidence of outbreaks in each context), and because the rules for each activity are based on an “individualized government assessment” of the governed conduct, the law is not generally applicable.

If the law is not generally applicable, then the 1993 U.S. Supreme Court case of Church of the Lukumi holds that a burden on a fundamental right is subject to “strict scrutiny” – meaning that the law must be narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest. “Narrowly tailored” means the government uses the least restrictive means possible to further the compelling interest. But if the government can further its social distancing objectives and allow more than five people to gather in a room for extended time period, it is not using the least restrictive means when it prohibits churches from doing so.

The reasons above are the same reasons that the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down Kentucky’s ban on in-person worship services and the Department of Justice has warned the State of California that its proposed re-opening plan does not sufficiently accommodate religious worship.

As the Sixth Circuit noted, the government need not be acting with animus toward religion for the law to be unconstitutional. The Sixth Circuit went out of its way to assume that the Kentucky Governor was acting in good faith and without hostility; even so, the court held that Kentucky’s the ban on worship was still unconstitutional.

In many ways, Governor Inslee has done a commendable job in response to the COVID pandemic. And his May 4 Safe Start proclamation recognized the crucial need for religious services and promised future lifting of restrictions:

But with two weeks having gone by since that Safe Start proclamation and numerous counties already in Phase 2, Governor Inslee still has not revised the unconstitutional restrictions on religious worship.

[1] Widely publicized cases in Oregon and Wisconsin are inapplicable here. Those cases were resolved on respective state law grounds, not because of any constitutional reason. Both Oregon and Wisconsin law impose time limits on governors’ emergency powers regarding health and safety, but Washington law does not. In those cases courts said that the governors in Oregon and Wisconsin had simply run out of time and had not followed the necessary procedural processes under their states’ laws to extend their stay-at-home orders. The Oregon ruling has been stayed pending appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court.

[2] In the 2017 case of Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, the U.S. Supreme Court noted “This is not to say that any application of a valid and neutral law of general applicability is necessarily constitutional under the Free Exercise Clause.” The court cited a 2012 case involving the internal affairs of a religious organization as an example. And at least in some cases, Article I, Section 11 of the Washington constitution provides greater free exercise protection than the First Amendment.